Published online: November 2019

Synthesis by: Dr Susan Walker, Manaaki Whenua–Landcare Research (walkers @ landcareresearch.co.nz)

- Recent land clearance has laid waste to native ecosystems across significant areas of the inland South Island, destroying already tenuous endemic species populations and creating a major conservation burden for future generations (Figure 1)

- Ecological research to identify, measure, understand, and communicate the effects of land use change is essential to halt and turn the tide

Figure 1. Land use intensification for dairying progressing in the Upper Clutha catchment in January 2014. The view is northwest across the Clutha River, to the Recommended Area for Protection (RAP) on the Luggate glacial outwash terraces, a critically endangered rare ecosystem. This was the largest remaining area of cushionfield and short tussock grassland in the Queenstown Lakes District, and was entirely cleared for dairying just weeks after this photo was taken (Peter Scott; Above Hawkes Bay).

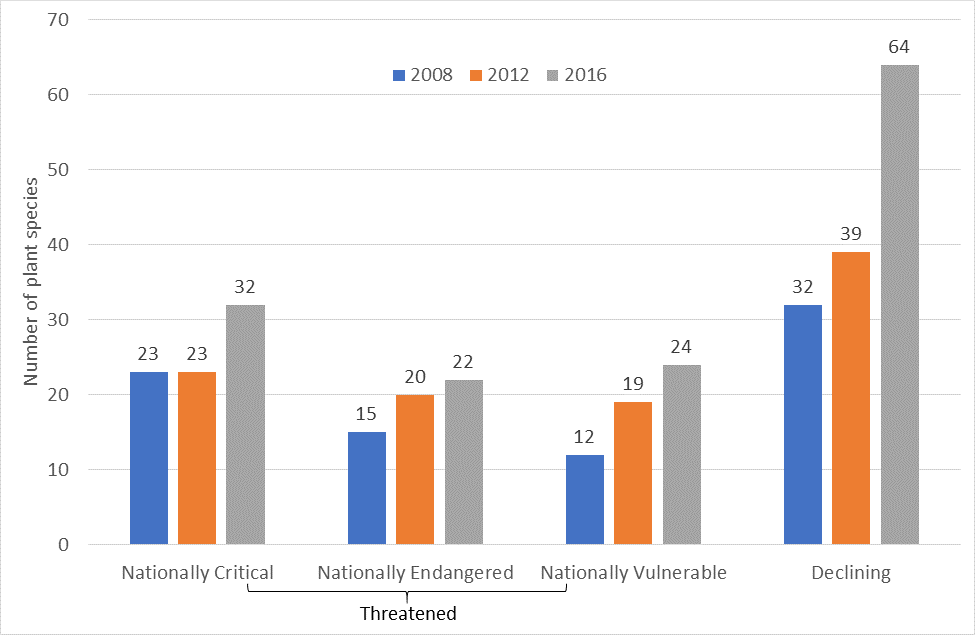

Vascular plants resist extinction: they have long-lived life stages, versatile reproductive systems, and are often amenable to domestic cultivation. But a suite of indigenous plant species endemic to New Zealand’s dryland zone has recently rocketed up the national threat rankings (Figure 2). This trend indicates that something is seriously amiss. That ‘something’ is large-scale land use intensification across the last two decades.

Land use change in South Island drylands has been a perfect, well-predicted storm. High-level drivers have been the dairy boom, large-scale privatisation of native ecosystems on crown land in high country tenure review, and a set of unprepared and conflicted central and local government agencies, guided by ambiguous legislation and symbolic policies that have wedged open the door to development.

Figure 2. Numbers of plant species in Southland, Otago and Canterbury high country that were listed as Threatened and Declining across three recent assessments; most of these species are specialists of the dryland zone (source: Harding et al. 2019).

These forces can seem too overwhelming for ecological scientists to influence, and the damage to native dryland ecosystems over the last decades is irreparable. But there are tenuous indications that the tide may be starting to turn, and that ecological research has a role to play. For example, some District Councils (all credit to Queenstown Lakes and Mackenzie) have used science to improve, and then influentially defend, their District plans. Also, government has just admitted the ecological cost of high country tenure review for dryland biodiversity, and ended it! Both seemed improbable a decade ago.

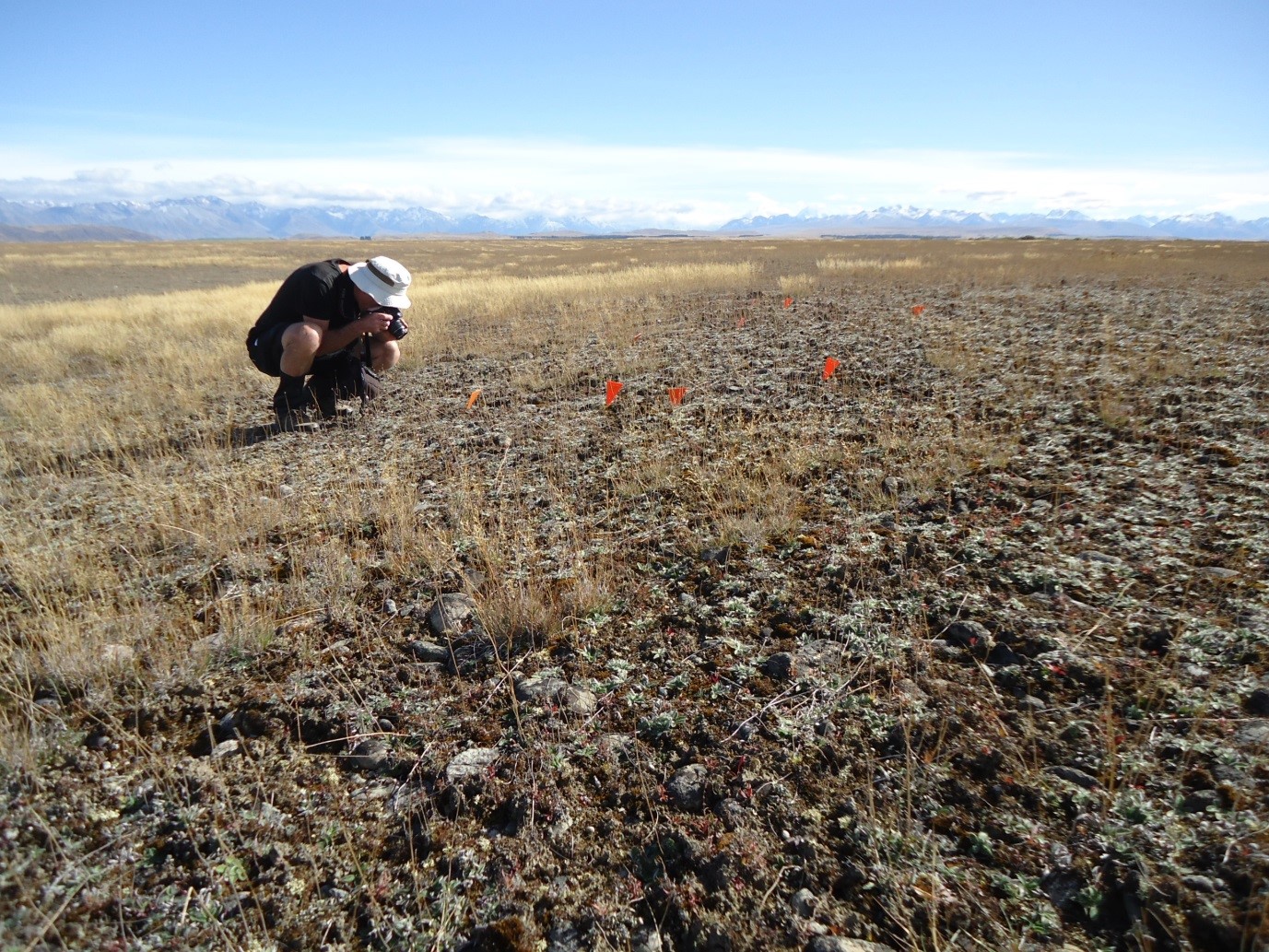

But there remains a long way to go. The remaining ecosystems of the inland South Island drylands are nationally significant – where else but the Mackenzie Basin can you record 12 threatened plant species within 100 metres of the vehicle, and a further three at the next stop? Yet they pose difficult challenges for researchers: choosing questions that will be influential at the right scales; hanging in for the long haul (because research outcomes take so long); and robust relationships with motivated partners to inform the right decision-makers. One doesn’t always pick winners; funding timeframes are limited; partners get burned out.

In my opinion, the most important and influential ecological questions to tackle now involve cumulative, landscape-wide effects of land use change on the persistence of native flora and fauna. Fertile topics include edge and offsite effects of land use, and the movements of wildlife, pests and diseases across fragmented landscapes. Research has just scratched the surface; the field is wide open.

Figure 3. We recently collected leaf samples of the ultimate invisible plant, Lepidium solandri (Nationally Critical), for genetic analysis to determine how far white rust Albugo candida has spread across the Mackenzie Basin, now the plant’s last stronghold. Research identifying New Zealand’s rare ecosystems (Williams et al. 2007) and showing that mouse ear hawkweed is not a threat to persistence of indigenous dryland species (Walker et al. 2016) was influential in new landscape planning rules (‘Plan Change 13’) that now require resource consent for pastoral intensification and agricultural conversion in Mackenzie District (Photo: Susan Walker).

References

Brower A 2008. Who owns the high country? Craig Potton, Nelson.

Brower A, Sprague R, Vernotte M, McNair H 2018. Agricultural intensification, ownership, and landscape change in the Mackenzie Basin. Journal of New Zealand Grasslands 80:47-54.

Harding MAC, Head NJ, Walker S 2019. Submission on enduring stewardship of crown pastoral land discussion document. Crown Pastoral Lands Consultation. Thursday 11 April 2019.

Walker S, Brower AL, Clarkson BD, Lee WG, Myers SC, Shaw WB, Stephens RTT 2008. Halting indigenous biodiversity decline: ambiguity, equity, and outcomes in RMA assessment of significance. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 32:225-237.

Walker S, Price R, Stephens RTT 2008. An index of risk as a measure of biodiversity conservation achieved through land reform. Conservation Biology 22:48-59.

Walker S, Brower AL, Stephens RT, Lee WG 2009. Why bartering biodiversity fails. Conservation Letters 2:149-157.

Walker S, Comrie J, Head N, Ladley KJ, Clarke D 2016. Hawkweed invasion does not prevent indigenous non-forest vegetation recovery following grazing removal. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 40: 137-149.

Weeks ES, Walker S, Dymond JR, Shepherd JD, Clarkson BD 2013. Patterns of past and recent conversion of indigenous grasslands in the South Island, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 37: 127-138.

Williams PA, Wiser S, Clarkson B, Stanley MC. New Zealand's historically rare terrestrial ecosystems set in a physical and physiognomic framework. New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 2007 Jan 1:119-28.